The Fire Crisis in Western Australia

Broadscale prescribed burning is unsustainable in a warming, drying climtate.

The WA Government’s fire management strategy is to maintain a fuel age of LESS THAN six years since last burnt in AT LEAST 45% of the landscape across the three south-west forest regions.

This equates to burning approximately 200,000 hectares of the southwest landscape on an annual basis.

These burns are meant to make us safer. Instead, they are destroying biodiversity, driving wildlife toward extinction, polluting our air, and having minimal effect on reducing fire risk, particularly in extreme fire weather.

Broadscale prescribed burning is unsustainable in a warming, drying climate

Why This is a Crisis

WA’s Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) uses fire extensively throughout southwest WA to burn vast areas of forests, woodlands and other biodiverse ecosystems each year through an area target system.

But independent reviews reveal

-

Biodiversity is under threat.

Threatened species like numbats and Western ringtail possums are being killed in prescribed burns and their habitats destroyed (Leeuwin Group, 2019). -

Communities are suffering.

Smoke has caused more premature deaths than wildfires in the southwest (Johnston et al., 2020). -

Safety isn’t guaranteed.

Major escaped prescribed fires like Margaret River 2011 swept through treated areas despite years of burning (IGEM, 2015).

A Timeline of Prescribed Burning in WA

Traditional Aboriginal burning practices in WA were suppressed by colonial laws and practices starting as early as the mid-19th century.

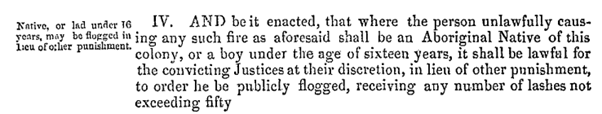

WA Bushfire Regulations were passed in 1847 which limited Aboriginal cultural burning practices and punished Aboriginal people for lighting fires, including public flogging: “An Ordinance to diminish the Dangers resulting from Bush Fires.”

Source: https://www.legislation.wa.gov.au/legislation/statutes.nsf/main_mrtitle_10973_homepage.html

Some settlers born 1901-1930 adopted and adapted Aboriginal burning methods:

- Season: autumn after first rains

- Frequency: mostly 3-4 yrs (2/3-8/10)

- Size: mostly 10-50 acres (0.4-20 hectares)

- Patchiness: high

Source: Abbott, 2003.

Broad area prescribed burning of southwest WA forests became formal policy in the mid-1950s.

The target to burn 200,000 hectares was developed in the late 1970's and early 1980's by the WA Forests Department and formally adopted by a Ministerial Review Panel in 1994.

It was notionally set by the average number of prescribed burning opportunities that could be expected to present themselves, the resources available to undertake them and an estimation of how much of the landscape needed to be maintained in a low fuel condition to reduce the risk of landscape scale bushfires.

This target equates to approximately 45% of the southwest landscape to have less than six year old fire ages.

Research shows no reliable link between total area burned and wildfire extent (Campbell et al., 2022).

What Indigenous Fire Knowledge Teaches Us

- Cool, small, patchy fires left escape routes for wildlife.

- Seasonal timing ensured renewal, not destruction.

- Sacred forests like karri and tingle were protected, never intentionally burned.

Reform must mean listening to Indigenous voices; respecting and supporting cultural fire knowledge, values and practices.

What’s Being Lost

- Fire regimes that cause declines in biodiversity have been nationally recognised as a key threatening process.

- Prescribed burns in Warrungup Spring Reserve in Mandurah and Perup east of Manjimup destroyed threatened populations of 'critically endangered' ringtail possums and 'vulernable' numbats.

- Black cockatoos and other hollow-dependent fauna lose nesting hollows when old growth trees collapse after burns.

- Frequent fire keeps forests permanently young and dense, making them more flammable.

- Between 2002–2017, prescribed burn smoke caused 21 premature deaths, compared to 4 from wildfires in the same period (Johnston et al., 2020).

- Annual smoke haze costs WA an estimated $24 million in hospital visits and lost productivity (Johnston et al., 2020).

- Children, the elderly, asthmatics and those with pre-existing illnesses are especially vulnerable.

Myths About Prescribed Burning

Myth

Fact

Myth

Fact

Myth

Fact

The Climate Cost of Burning

- All of Western Australia has warmed since national records began in 1910. Average temperature has increased by 1.3 °C since 1910, leading to an increase in the frequency of extreme heat events.

- Western Australia has a rapidly warming and drying climate, with 20% less winter rainfall in southwest WA since 1970, accelerating to 26% since 1999.

- The decline in southwest WA has been larger than anywhere else in Australia.

- Many parts of the southwest have had the lowest rainfall deciles recorded for 125 years, since 1900 from July 2023 to June 2025.

- As a consequence, extensive areas of native vegetation, wetlands and waterways have suffered severe drought and heatwave impacts.

- There has been a long-term increase in extreme fire weather and in the length of the fire season across large parts of Australia since the 1950s.

- WA is expected to have longer fire seasons, with around 40% more very high fire danger days.

Community Voices

If Nothing Changes

If WA continues blanket broad-scale burning every year

Species like the numbat and western ringtail possum could face local extinction within a decade (Leeuwin Group, 2019).

Old growth forests will continue to collapse and deteriorate and be replaced by dense, highly flammable regrowth

Communities will face an ongoing smoke-related health crises.

This isn’t a distant risk. It is happening now — and accelerating.

Why Change is Urgent

Abandoned its hectare target in 2015, adopting a risk-based approach (Safer Together) that targets burns in area where they matter most (IGEM, 2015).

Uses Bush Fire Risk Management Plans that prioritise community safety, not annual quotas (NSW RFS, 2020).

California and Portugal emphasise rapid detection, early suppression, and cultural fire.